Record collections an unexpected launchpad for careers, movements

Back in the 1980s I had a chance to flip through one of the most influential record collections I’ve ever seen.

It wasn’t large, but it was eclectic and well cultivated.

In it were records by big band leader Nelson Riddle, the Mariachi Vargas, Lola Beltran, Lalo Guerrero and popular Mexican recording artists, American standards, the musical The Pirates of Penzance, opera diva Maria Callas and a few choice classical selections.

The collection belonged to Linda Ronstadt‘s dad, Gilbert Ronstadt. And with the exception of her country and rock rocordings, the bulk of Linda’s recording career came from the music she heard playing on her father’s record player growing up.

Minimalist classical composer Phillip Glass is the son of a record store owner who had a shop in New York City. Glass’ father was also an eclectic listener who stocked his store with every sort of music, from popular favorites and classical works to music from around the globe. Glass once told me in an interview for the Tucson Citizen that when certain albums didn’t sell, his dad would open them and put them on the turntable to see if he could figure out why. Some were examples of world music from India and Africa. They became things that Glass and his father enjoyed, and the foundations of Glass’ own pursuits as a composer.

Navajo-Ute flutist R. Carlos Nakai‘s father had a radio show on the tribal station. He would seek out Native American recordings of all sorts. That’s where the younger Nakai first heard the cedar Native American flute that would become his musical voice, and where he studied the covers of a record label called Canyon Records that would become the leading producer of his recordings. Hanging arond the studio with his dad, going through the records of Native American music gave Nakai perspective on who he was and what his people had created.

Navajo-Ute flutist R. Carlos Nakai‘s father had a radio show on the tribal station. He would seek out Native American recordings of all sorts. That’s where the younger Nakai first heard the cedar Native American flute that would become his musical voice, and where he studied the covers of a record label called Canyon Records that would become the leading producer of his recordings. Hanging arond the studio with his dad, going through the records of Native American music gave Nakai perspective on who he was and what his people had created.

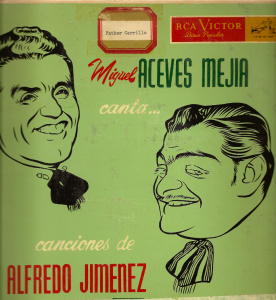

This week I paid a visit to the man whose record collection started the youth mariachi movement – Monsignor Arsenio Carrillo of Tucson – as part of the interviews for The Mariachi Miracle. Back when Carrillo was a young priest, he played his favorite mariachi recordings at the rectory, catching the attention of a young priest from Schenectady, N.Y. named Charles Rourke. Rourke had studied jazz piano and had a well cultivated ear. Rourke followed the sound down the hall and knocked on Father Carrillo’s door, asking in a less than priestly way what that music was.

“What the hell is that,” Rourke demanded.

“This is mariachi,” Carrillo replied, and proceeded to fill the Irish American priest in on the music that Carrillo had come to love, listening with his mother to the Spanish radio station while growing up in Tucson’s Barrio Anita.

Rourke hijacked then-Father Carrillo’s records and began listening intently. The next day he was playing tunes out on the piano. And withing a few weeks he’d bought himself a guitarrón and began learning to play that big bass guitar.

It would be several years before that growing musical appreciation would translate into the birth of America’s first youth mariachi, Los Changuitos Feos. But 50 years, 13 genrations of players and a half million dollars in college scholarships later, Los Changuitos Feos goes on.

The old 10″, LPS, 78s and 45s from Monsignor Carrillo’s collection became the aural model for that first generation of young players.

Goes to show, you never know who’s listening when you play your favorite recordings, and what might come from that chance encounter in time.